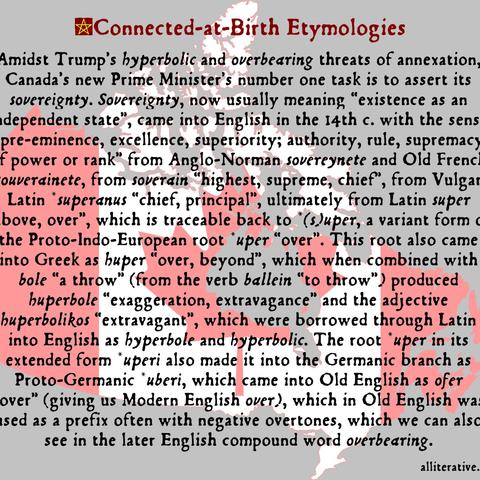

I find it amusing that most people who write articles against passive voice use passive voice in those very articles, but the history I learnt from #MastoDaoine showed me a completely different perspective on the whole thing.

In some languages, there’s are so-called deponent verbs — verbs whose forms look grammatically passive but have active meanings. They are pretty common in Latin, but in Old Irish passive forms were apparently so widely used that they completely supplanted former active forms for many verbs.

Here’s how a normal, non-deponent verb can work:

“Crenaid ind notaire libru” — “The scribe(ind notaire — nom.sg.) buys (crenaid — verb, present, 3sg, active) books (libru < lebor — acc.pl.). Old Irish allow omitting the subject because it has unique verb forms for every person and number, so one can also say “crenaid libru” — “an unspecified person, she or he, buys books”.

“Crenar libair lasin notaire” — “Books(libair — nom.pl.) are-bought (crenar — verb, present, 3sg, passive) by-the (lasin — prep+def.art) scribe (notaire — acc.sg.)”. The ‘r’ ending is a sign of a passive form.

Now let's consider this sentence:

“Ro-cluinethar ind notaire inna bríathra”. There’s an ‘r’ at the end of ‘ro-cluinethar’, which implies that it’s in passive voice and originally it would mean “the words are heard by the scribe”. In reality, it’s “The scribe(ind notaire — nom.sg.) hears(ro-cluinethar) the words(inna bríathra — acc.pl.)”. “Ro-cluinethar inna bríathra” means “she or he hears the words”, not “the words are heard”.

But Old Irish people certainly loved their passive voice and quite a few of those deponent verbs developed new, "twice-passive" endings. “Ro-cluinter inna bríathra lasin notaire” — “The words are heard by the scribe”. Some verbs do not have special twice-passive endings or they are not attested in manuscripts, so “labraithir ind notaire inna bríathra” may mean “the scribe speaks the words” or “the words are spoken by the scribe”. In a sense, both mean the same thing so there's no ambiguity there...

1/2

THE EMOJI WORKSHOP

to take place August 29 2025, University of Oslo